How Hemodialysis Works! 4 Key Questions to Help You Understand Life-Saving Technology

When hearing the term "hemodialysis," some may feel unfamiliar. Yet, hemodialysis is a crucial life-supporting technology and a beacon of hope for extending life. We have compiled several questions that the public is most concerned about, guiding you to understand this medical technology that appears "complex" but has saved countless lives.

What is hemodialysis and what is its function?

You can imagine the hemodialysis device as an "artificial kidney" or a precise "blood cleaning machine," with its core function being to replace some of the functions of a damaged kidney.

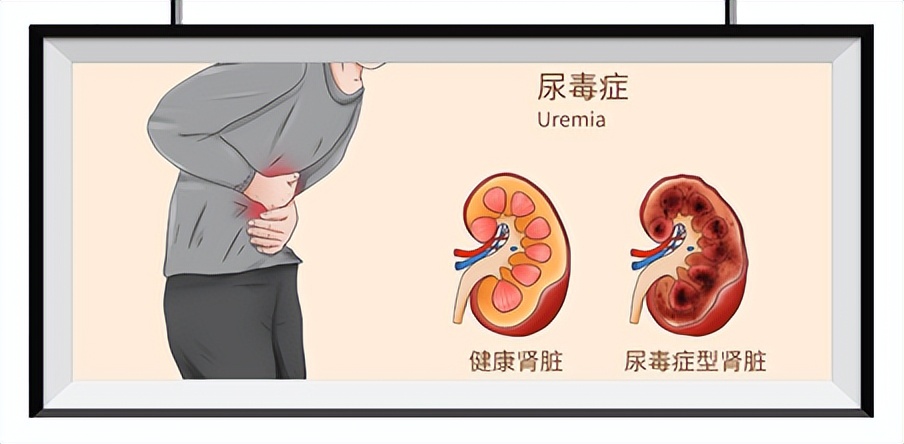

Healthy kidneys act as the body's built-in "precision filters," capable of removing toxins such as urea and creatinine produced during metabolism, expelling excess water, while maintaining the balance of electrolytes like blood potassium and sodium, and also secreting hormones such as erythropoietin to regulate physiological functions.

When kidneys fail due to chronic nephritis, diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive kidney damage, and other conditions, resulting in severe functional failure (known as end-stage renal disease, commonly referred to as uremia), toxins and excess water accumulate in the body, causing symptoms such as fatigue, edema, nausea, vomiting, and difficulty breathing, which can be life-threatening in severe cases. At this point, hemodialysis becomes a "life-saving measure": it draws the patient's blood out of the body through a dedicated circuit, passes it through a core component called a "dialyzer" (which contains countless semi-permeable membrane fibers), and uses the principles of diffusion and convection to remove toxins and excess water from the blood, while simultaneously regulating electrolytes and acid-base balance, before finally returning the purified blood to the patient's body.

As the most mainstream dialysis method currently, hemodialysis has clear treatment protocols: a vascular access must be established before treatment, and patients need to go to the hospital 2~3 times a week, completing 4 hours of blood purification each time. Its advantage is high toxin clearance efficiency, but its disadvantages are also obvious—requiring frequent hospital visits and relatively strict dietary control during treatment (such as limiting water, salt, and high-potassium food intake).

In addition to hemodialysis, end-stage renal disease patients have another option—peritoneal dialysis. This method is more suitable for home use, primarily by implanting a dialysis catheter into the peritoneal cavity to utilize the body's own peritoneum to filter blood. Patients can change the fluid themselves at home daily or use a machine for nighttime treatment, offering more flexible scheduling and looser dietary restrictions. However, its main disadvantage is that improper operation can lead to peritonitis; if sterile operation is maintained, the probability of peritonitis can be significantly reduced.

In clinical practice, doctors will choose the most suitable dialysis plan based on the severity of the patient's condition, physical tolerance, and personal preferences.

Once you start dialysis, do you have to do it for life?

The answer is "not necessarily," and it depends on the nature of the patient's kidney failure—is it acute or chronic.

1. Acute Renal Failure (Acute Kidney Injury) This condition is often triggered by sudden factors, such as severe infections, drug toxicity, urinary tract obstruction, or severe glomerulonephritis. With prompt and effective treatment, the renal impairment is often reversible. Hemodialysis administered over a period of time helps eliminate accumulated toxins from the body, reduce the kidney’s burden, and create an opportunity for the kidneys to rest and recover. Once kidney function gradually improves to meet the body’s basic needs, there is a chance to discontinue dialysis entirely.

2. Chronic Kidney Failure (Uremia Stage): This is a more common clinical scenario: kidney damage is long-term and progressive. When kidney function declines to an irreversible extent, it means the kidneys can no longer perform metabolic tasks independently, and patients need lifelong "kidney replacement therapy"—either long-term regular dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) or waiting for a suitable kidney source for kidney transplantation.

Simply put, only patients in the uremic stage of chronic kidney failure are likely to need "life-long dialysis"; for acute kidney failure patients, dialysis is more of a "transitional treatment."

Is the hemodialysis process painful, and how exactly is it performed?

The dialysis process itself is usually not painful; the patient's "discomfort" comes more from the preparation before treatment and long-term self-management.

1. Before dialysis: First establish the "lifeline" - vascular access

To perform hemodialysis, establishing a safe and unobstructed vascular access is the key to ensuring the smooth progress of the procedure, and it is referred to as the patient's "lifeline." There are two most commonly used types in clinical practice:

Arteriovenous fistula: This is the "preferred access" for long-term hemodialysis patients. Through a minor surgical procedure, one artery and an adjacent vein on the patient's arm are anastomosed, allowing arterial blood to flow into the vein. After 1 to 3 months, the vein will gradually "arterialize"—thicken its wall and widen its lumen, making it capable of withstanding the blood flow during dialysis and facilitating repeated needle punctures by nurses. The pain during puncture is similar to that of a regular injection or blood draw, and most patients can tolerate it.

Central venous catheter: Primarily used for "temporary or emergency situations," such as when a patient urgently needs dialysis but the arteriovenous fistula has not yet been established, or when the fistula becomes blocked or infected. The doctor will implant a soft catheter into the patient's neck or groin, with one end remaining outside the body to connect to the dialysis circuit. The advantage of this access is that it can be used immediately, but long-term use can easily lead to complications such as infection and thrombosis, so it is not recommended as a long-term access.

During dialysis: 4 hours of "peaceful waiting"

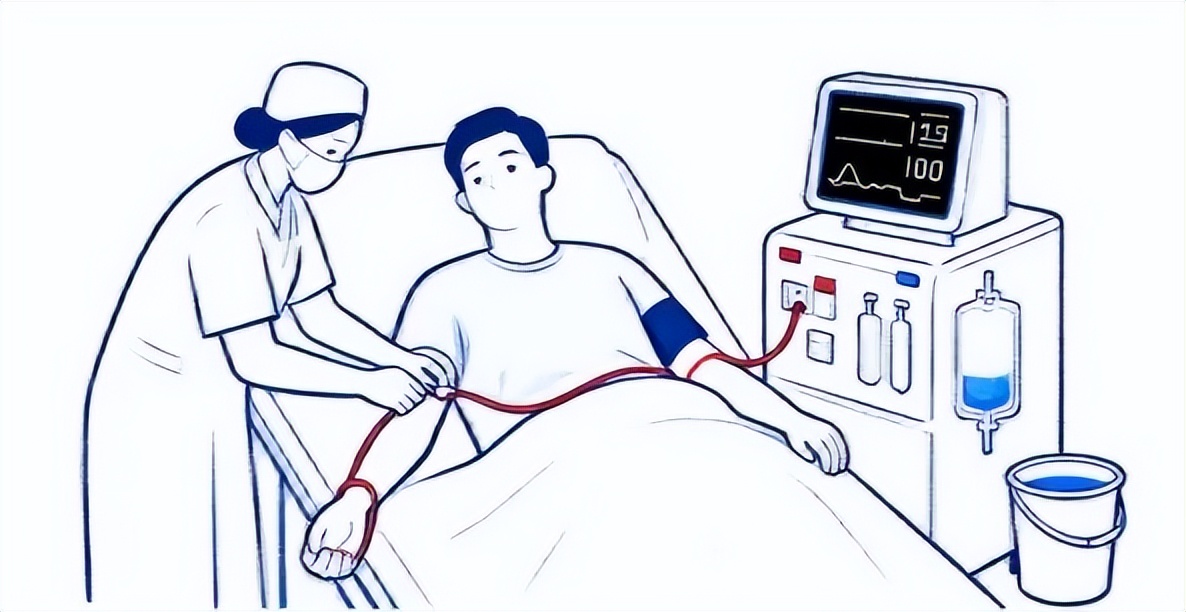

Before treatment, the nurse will first verify the patient's information, rinse the dialysis circuit and dialyzer with physiological saline to ensure the equipment is sterile; then, disinfect the vascular access site (such as the arm with an internal fistula), and then puncture the internal fistula (or connect the central venous catheter), introducing the patient's blood through a sterile tube into the dialysis machine.

During the treatment process, blood continuously flows through the dialyzer. After completing the removal of toxins and excess fluid, it is returned to the patient's body through another tube. Patients are usually lying on a bed or sitting in a chair, during which they can read, listen to music, watch TV shows, or even close their eyes to rest. The 4-hour treatment process is generally quite relaxing.

3. What situations make patients feel "pain"

The discomfort experienced by patients rarely comes from dialysis itself, but rather from two main points.

First is the long-term changes in lifestyle, such as the need to strictly control fluid intake (otherwise it can easily lead to edema and heart failure), and not being able to freely eat high-potassium foods like bananas, oranges, potatoes (to avoid hyperkalemia leading to arrhythmia).

Second, there are some complications, where some patients may experience low blood pressure, muscle cramps during dialysis, or skin itching after dialysis. However, with the advancement of modern dialysis technology, the incidence of these complications has been significantly reduced, and doctors will take timely intervention measures (such as adjusting dialysis parameters, supplementing calcium) to alleviate the patient's discomfort.

Can I live and work normally after hemodialysis?

Absolutely! The core goal of regular dialysis is not just "maintaining life," but also helping patients "return to normal life."

Many patients, after starting regular dialysis, have toxins and excess fluid removed from their bodies. Symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, and skin itching previously caused by uremia will significantly improve or even disappear. Appetite and physical strength gradually return, and quality of life can be significantly enhanced.

In daily life: Besides the fixed 2~3 times of dialysis per week, patients can live just like ordinary people, such as cooking, walking, shopping, or even traveling outside (contact the dialysis center at the destination in advance to schedule "travel dialysis").

At the work level: Many patients choose to return to work after achieving stable dialysis, especially those engaged in non-heavy labor such as writing and management. As long as they communicate well with their employers about work hours (e.g., avoiding dialysis days) and arrange their schedules reasonably, they can fully perform their job duties.

So, for patients and their families, there's no need to panic about kidney disease: fully understand dialysis knowledge, actively cooperate with treatment, manage diet and lifestyle well, maintain an optimistic mindset, and you can "coexist peacefully" with the disease, living out your own wonderful life.