How Did Ancient People Treat Cancer?

Modern people are no strangers to cancer. With the development of society, the incidence of cancer is increasing, yet the cure rate remains low. So, did cancer exist in ancient times? How did ancient people treat cancer?

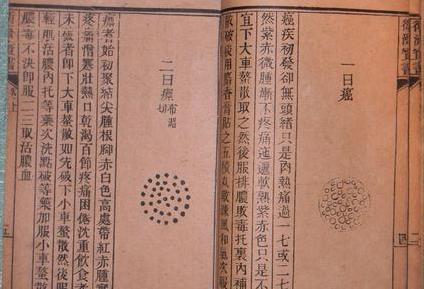

The Chinese character for "cancer" (癌) dates back to the Song Dynasty, with records found in "Wei Ji Bao Shu" and "Ren Zhai Zhi Zhi Fu Yi Fang Lun." The character for "tumor" (瘤) appeared even earlier, being mentioned in oracle bone inscriptions from the Yin and Shang periods.

Of course, the terms "cancer" and "tumors" as referred to by the ancients are not entirely the same as the modern understanding of cancer and tumors. The ancient terms such as "徵瘕积聚" (abdominal masses), "肾岩" (kidney cancer), "乳岩" (breast cancer), and "脏毒" (visceral toxin) are similar to what we now call cancer.

Zhu Danxi, one of the Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, recounted a story in his book "Ge Zhi Yu Lun" about a woman who, after marriage, had strained relationships with the female relatives in her household, leading to daily feelings of depression. Ten years into her marriage, she developed a lump in her breast, which gradually hardened over time and eventually progressed into "奶岩" (breast cancer). "奶岩" is the same as "乳岩," which corresponds to what is now known as breast cancer.

The ancients believed that this condition was caused by depression and anger damaging the liver, and excessive worry damaging the spleen, leading to qi stagnation and phlegm accumulation. In traditional Chinese medicine, breast cancer is classified into six patterns, each with different treatment methods. For instance, in cases of qi stagnation and phlegm accumulation, the treatment focuses on soothing the liver, regulating qi, resolving phlegm, and dispersing masses. For cases of toxic heat accumulation, the approach involves clearing heat, detoxifying, reducing swelling, and dispersing hard nodules.

Wang Kentang's "Zheng Zhi Zhun Sheng" from the Ming Dynasty also records a case of male breast cancer. It describes a scholar who, after failing the imperial examinations multiple times, became perpetually despondent. Soon, he noticed a discharge from his left nipple, and shortly afterward, a lump appeared beside it. Due to a lack of timely treatment, the lump gradually enlarged, ulcerated, and eventually developed into breast cancer.

This also shows that depression is an important cause of breast cancer.

The ancient understanding of cancer was different from today's. Traditional Chinese medicine theory did not specifically discuss cancer, but included various types of cancer within different diseases, such as accumulation and aggregation.

Strictly speaking, accumulation and aggregation are two different disorders. "Accumulation" refers to tangible masses that are fixed in location and cause localized pain, while "aggregation" refers to intangible masses that come and go without a fixed location and cause shifting pain. Due to the close relationship between accumulation and aggregation, they are often discussed together. Modern abdominal tumors are mostly included within the category of "accumulation," while conditions such as hepatosplenomegaly and hypertrophic intestinal tuberculosis caused by various reasons also fall under the scope of "accumulation." Thus, accumulation and aggregation are collective terms for a class of related disorders, rather than referring to a single disease as in Western medicine.

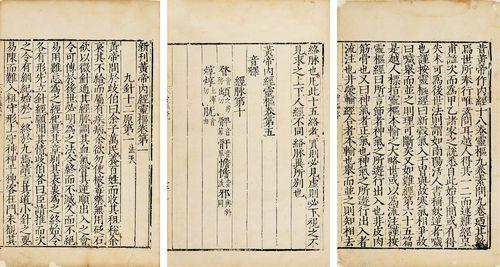

Regarding the treatment of accumulation and aggregation, discussions began as early as the Qin and Han dynasties in the *Yellow Emperor's Inner Classic*, and by the Ming dynasty, a complete system of diagnosis and treatment had been established.

The progression of accumulation disorders can be divided into three stages: early, middle, and late, and further classified into five syndrome patterns. For instance, the liver qi stagnation syndrome, which falls under the category of accumulation syndromes, can be effectively treated with Xiaoyao San to soothe the liver, relieve depression, regulate qi, and disperse masses. In contrast, the syndrome of deficiency with blood stasis, which is classified as a mass syndrome, presents symptoms similar to advanced abdominal cancer. It is treated with Bazhen Tang combined with Huaji Wan to tonify qi and blood, promote blood circulation, and resolve stasis, although the prognosis remains poor.

The incidence of cancer in ancient times was significantly lower than in modern times, with few well-documented cases scattered across historical and medical texts. For example, Sima Qian’s "Records of the Grand Historian" documented a case where the Han Dynasty physician Chunyu Yi diagnosed and treated stomach cancer, while the "Book of Jin" recorded a case of surgical treatment for an ocular sarcoma.

Ancient people employed various methods to treat cancer, such as acupuncture, fumigation, external application, oral administration of medicines, and even surgery, though oral administration of traditional Chinese medicine remained the primary approach. With the advent of modern times, the emergence of Western medicine posed a significant challenge to traditional Chinese medicine but also spurred its further development. Today, the dialectical system of Chinese medicine has become increasingly refined, with a clearer understanding of cancer and a growing role in the treatment process.

It is believed that in the future, traditional Chinese medicine will play an even greater role in cancer treatment.