Women Who Have Lost Their Uterus: How Do They Differ from Normal Women? These Changes May Be Irreversible.

Losing the uterus affects women beyond fertility; many of the physiological changes that subtly occur are difficult to reverse.

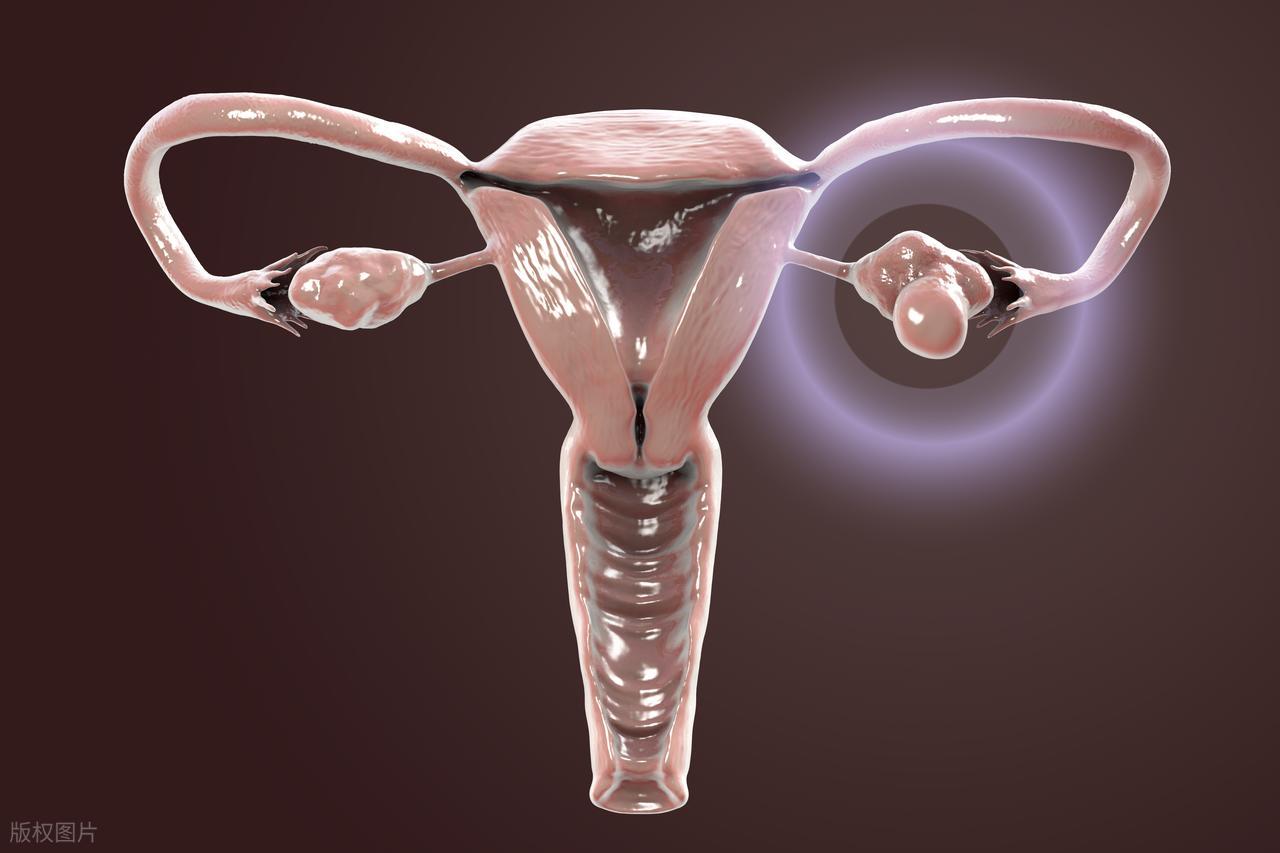

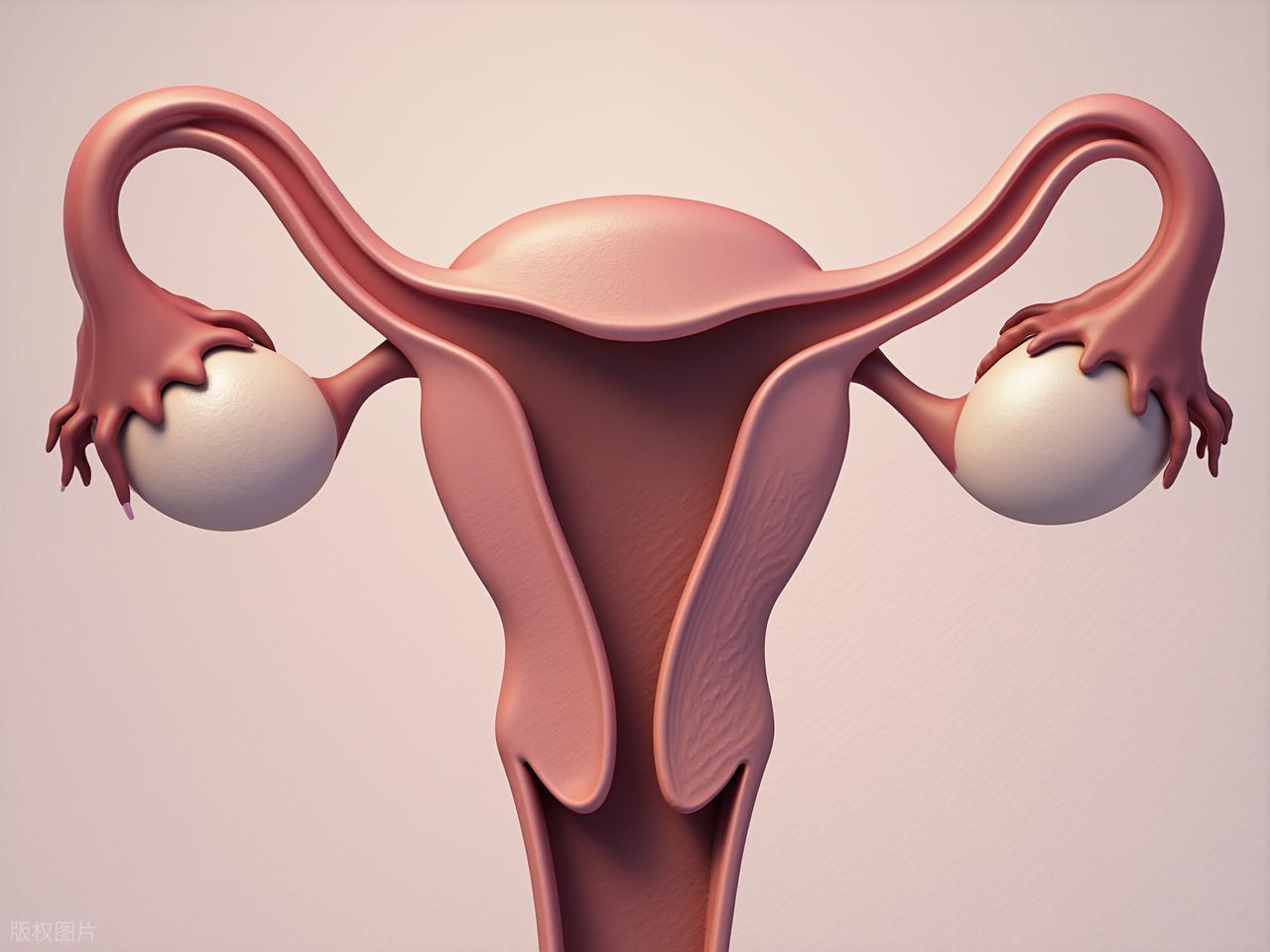

As a female-specific internal reproductive organ, the uterus is not only a "greenhouse" for nurturing embryos but also a crucial organ for regulating endocrine function and maintaining pelvic floor structural stability.

When a woman has to have her uterus removed due to disease, her body undergoes a series of changes compared to normal women. These changes stem from the loss of the uterus's physiological functions, some of which may not be fully restored through subsequent interventions.

First, the permanent loss of fertility is the most direct difference.

In normal women, the uterus is the only site for implantation of the fertilized egg and embryonic development. The cyclical thickening and shedding of the endometrium result in menstruation, while also providing nourishment and protection for the fetus for up to ten months.

After removal of the uterus, regardless of whether ovarian function is preserved, the foundation for bearing life is lost. Even if eggs are released normally and combine with sperm, implantation and development cannot occur. This change is irreversible for women who desire fertility.

Second, disruption of the endocrine system and decline in ovarian function are among the core changes.

The uterus is not merely an "accessory organ." It secretes a variety of hormones such as prostaglandins, prolactin, and insulin-like growth factors, which are involved in the regulation of the menstrual cycle and the balance of overall metabolism.

More importantly, the uterine artery supplies 50%–70% of the blood flow to the ovaries. Following a hysterectomy, ovarian blood flow significantly decreases, directly accelerating follicular atresia and leading to an earlier decline in ovarian function.

Clinical data indicate that patients who have undergone a hysterectomy face a 1.8–2.3 times higher risk of ovarian function decline, with the average age of menopause advancing by 1.9–3.7 years. Consequently, perimenopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, and insomnia tend to appear earlier and more prominently. Once this process begins, it is difficult to fully reverse through non-hormonal treatments.

The risk of pelvic floor dysfunction is significantly elevated, which is also a difference that cannot be ignored.

Normally, the uterus is located at the center of the pelvic cavity, positioned between the bladder and the rectum, and serves as the central anchoring point for the pelvic floor muscle groups. It acts like a "central scaffold," maintaining the normal position of the pelvic organs.

After uterine removal, the anatomical structure of the pelvic floor is disrupted, the vaginal apex loses its support, and the mechanical balance of the bladder and rectum is compromised. This leads to a substantial increase in the risk of stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Data indicate that the risk of anterior vaginal wall prolapse increases 2.3-fold after hysterectomy, with the incidence of stress urinary incontinence reaching as high as 40%. Patients may experience symptoms such as urine leakage when coughing or sneezing, or feelings of lower abdominal sagging and a sensation of prolapse after prolonged standing. Even with pelvic floor rehabilitation exercises, symptoms can only be alleviated, and it is difficult to fully restore the pre-operative pelvic floor support state.

Additionally, vaginal microecological imbalance and frequent gynecological inflammation are also common changes.

Following hysterectomy, particularly in patients who also have their cervix removed, the vaginal apex is surgically closed. Combined with declining ovarian function leading to reduced estrogen levels, the vaginal mucosa gradually atrophies, the population of lactobacilli decreases, vaginal pH rises to above 6.5, and the natural antibacterial barrier is compromised.

This makes women who have lost their uterus more prone to vaginitis, experiencing symptoms such as vaginal dryness, itching, and abnormal discharge. Furthermore, the likelihood of recurrent inflammatory episodes is significantly higher than in women with intact uteri. Long-term management through local care or hormone replacement therapy is often required for symptom relief, yet it cannot restore the original balance of the vaginal microecology.

The increase in long-term health risks is also worthy of attention.

After hysterectomy, changes in hormone levels affect bone metabolism and cardiovascular health, leading to alterations in lumbar spine stress distribution that degrade trabecular bone structure, increasing the risk of osteoporosis;

At the same time, the protective effect of insulin-like growth factor on vascular endothelium diminishes, accelerating the development of atherosclerosis and correspondingly raising the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Although these long-term effects may not manifest immediately, they become increasingly apparent with age and, once organic changes have occurred, are difficult to completely reverse. Early intervention can only delay progression.

While the psychological impact does not directly constitute a physiological difference, it is closely intertwined with bodily changes.

Some women may experience a change in self-identity after losing their uterus, feeling "incomplete" and subsequently developing emotions such as low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. If this psychological state is not addressed in a timely manner, it can further affect endocrine and immune system functions, creating a vicious cycle.

It is important to clarify that hysterectomy is a crucial treatment for conditions such as cervical cancer, severe uterine fibroids, postpartum hemorrhage, and other diseases. When a disease threatens life, removing the uterus becomes a necessary choice.

Postoperative symptoms can be significantly alleviated, and long-term health risks can be reduced through scientific interventions, such as hormone replacement therapy, pelvic floor rehabilitation exercises, and regular health monitoring.

For women who have undergone a hysterectomy, these changes represent objective physiological adjustments rather than "deficiencies." Accepting bodily changes, adhering to postoperative care, and managing health effectively can still maintain a high quality of life.