Blood in Stool Shocks the Night! It's Not "Hemorrhoids" Bleeding, But "Rectal Vascular Ectasia" Playing Tricks

"Boom!" The heavy rain pounded against the truck's windshield as 48-year-old Master Zhang clutched the steering wheel, when sudden abdominal pain struck. Pulling over at a rest area restroom, his heart sank as he stared at the blood swirling in the toilet bowl—this marked his 17th episode of bloody stools in just six months.

The first time he noticed it was after a long-distance haul when he saw blood on the toilet paper. Convinced that "all truckers have hemorrhoids," he bought a tube of hemorrhoid cream at a roadside store. But after applying it for three weeks, the rectal bleeding went from "occasional" to "every bowel movement," and sometimes he'd see black spots when standing up after squatting. His wife, Sister Wang, anxiously flipped through medical records all night: "Let's go to the hospital!"

The community hospital doctor listened to the symptoms and prescribed hemorrhoid-suppressing medication without even performing an examination: "Drink less alcohol and rest more." But on the fifth day of taking the medicine, Master Zhang suddenly experienced excruciating abdominal pain while driving on the highway. After pulling over, he found the toilet bowl soaked in blood—so much so that he had to lean against the wall to avoid collapsing. Sister Wang, in tears, managed to secure an appointment with a gastroenterology specialist at the city hospital. During the painless colonoscopy, the doctor only noted "slightly red rectal mucosa" and diagnosed it as "chronic enteritis," advising a simple medication adjustment.

For the next month, Master Zhang quit smoking and drinking and ate vegetables with every meal, yet the bloody stools persisted like an inescapable shadow. One day after returning from a delivery, he collapsed from dizziness the moment he sat down. That night, Sister Wang urgently contacted Chief Chen from the proctology department at a traditional Chinese medicine hospital. In the consultation room the next day, after reviewing a thick stack of medical records, Chief Chen tapped the desk and asked, "Does it hurt when you pass blood? Do you feel bloated?" "No pain, just bloating, and my weight hasn’t dropped." This answer made Chief Chen’s expression turn serious: "Get an enhanced CT scan to check the blood vessels."

Three days later, the CT results came in: three dilated blood vessels with diameters of 4–6 mm were found in the lower rectum, resembling fragile "tiny nets." "This is rectal vascular ectasia—not hemorrhoids or enteritis," Chief Chen explained, pointing at the images. At that moment, Master Zhang’s heart, burdened for half a year, finally settled.

### 1. Rectal Vascular Ectasia: The "Invisible Trap" of Pathogenesis and Pathology

As an intestinal bleeding disease prone to misdiagnosis, its pathogenesis and population characteristics have clear indications:

Core etiology: Dual effects of pressure and degeneration

Prolonged sitting (e.g., truck drivers, office workers), chronic constipation, and low-fiber diets can obstruct the rectal venous return pathway, causing sustained elevation of venous lumen pressure (normal rectal venous pressure is approximately 1.3 kPa, while in patients it may rise above 3.0 kPa), forcing compensatory thickening of the vascular wall. After age 40, the elastic fibers of the vascular wall gradually fracture, and the smooth muscle layer atrophies—like "aging rubber tubing"—losing its contractile hemostatic capacity. Any slight increase in abdominal pressure (e.g., defecation, coughing) may lead to rupture.

Pathological feature: "Malformed expansile network" of blood vessels

The diameter of normal submucosal rectal blood vessels is typically <1mm, but can enlarge to 3-8mm when affected by disease. The vascular walls demonstrate collagen fiber degeneration and increased endothelial cell gaps, with some vessels showing minor perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration, forming "fragile vascular clusters." Microscopic examination reveals shortened distance between dilated vessels and mucosal surface (separated by only 1-2 epithelial cell layers), making them highly susceptible to fecal friction damage.

Related condition: A "local signal" of systemic vascular issues

Approximately 35% of patients have underlying comorbidities: cirrhosis (portal hypertension doubles rectal venous pressure), chronic kidney disease (uremic toxins damage vascular endothelium), or congestive heart failure (venous return impairment). These patients exhibit more extensive vascular dilation with a 2.3-fold higher bleeding risk compared to typical patients.

II. Diagnostic tests: The critical step from "missed diagnosis" to "confirmed diagnosis".

Routine examinations are prone to "miss the mark," requiring targeted selection of precise methods:

Limitations of Routine Examinations: Why Are Diagnoses Missed?

Digital rectal examination can only detect lesions within 7cm of the anus and cannot distinguish vascular ectasia (tactile differences from normal mucosa are minimal); standard colonoscopy (white-light endoscopy) can only observe the mucosal surface—if vascular ectasia is not accompanied by erosion or ulceration, it is easily misdiagnosed as "mild congestion" (as in Mr. Zhang's initial colonoscopy), with a missed diagnosis rate exceeding 60%; fecal occult blood tests can only indicate bleeding but cannot pinpoint the cause.

2. Core Examinations: Three Types of Methods to Identify Lesions

Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI (preferred non-invasive examination): Intravenous contrast administration can clearly display the "enhanced vascular clusters" within the rectal wall, precisely locating the position, number, and diameter of dilated vessels with an accuracy rate of 89%, making it suitable for preliminary screening;

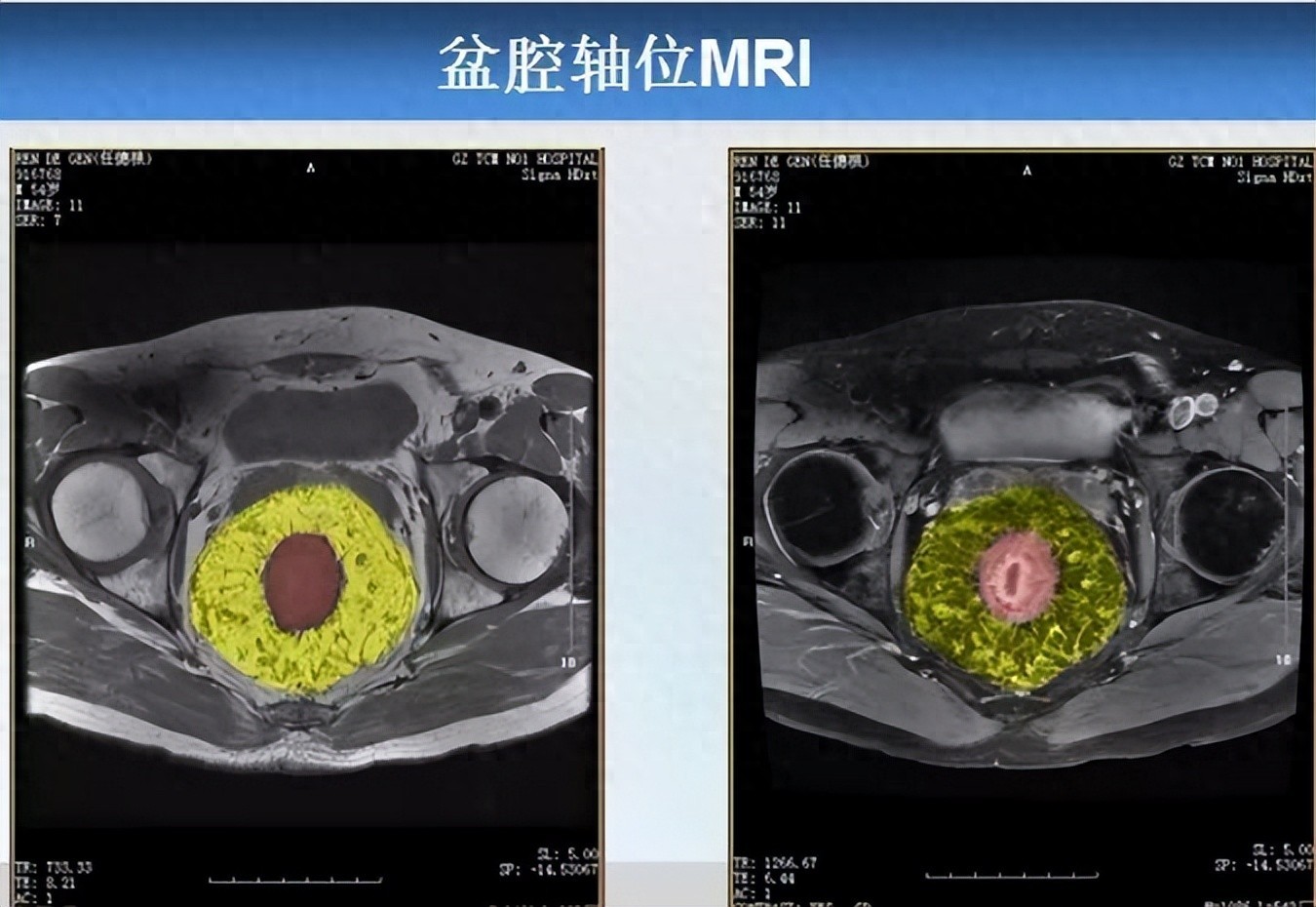

Pelvic MRI (plain scan + contrast-enhanced), as shown in the image above, reveals the following findings: In the mesorectal fat surrounding the middle and lower rectum (marked in red) (Note: Subsequent color processing was applied to the image, with mesorectal fat marked in yellow, same below), numerous "tadpole-shaped" ("bean sprout-like") cord-like, tortuous, and dilated vascular images are visible. Sagittal MRI similarly confirms these findings, demonstrating extensively dilated vascular structures within the mesorectum.

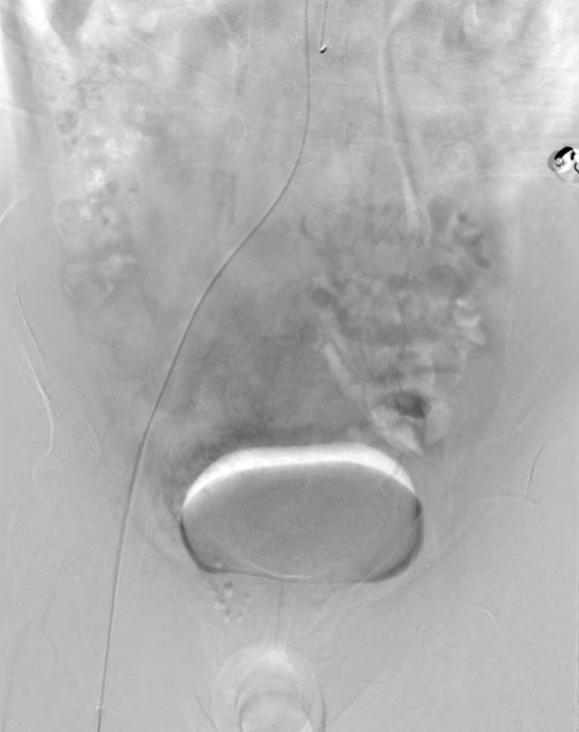

Angiography (gold standard for dynamic diagnosis): Suitable for patients with significant bleeding (daily blood loss >50ml) or those with concomitant vascular malformations. It allows dynamic observation of vascular blood flow direction, helps determine the presence of abnormal shunting, and provides evidence for surgical planning

Endoscopic ultrasonography (depth assessment): Capable of penetrating the rectal wall to visualize the depth (mucosal layer/submucosal layer) and extent of vascular dilation, preventing damage to deeper tissues during treatment, particularly suitable for patients scheduled for endoscopic therapy.

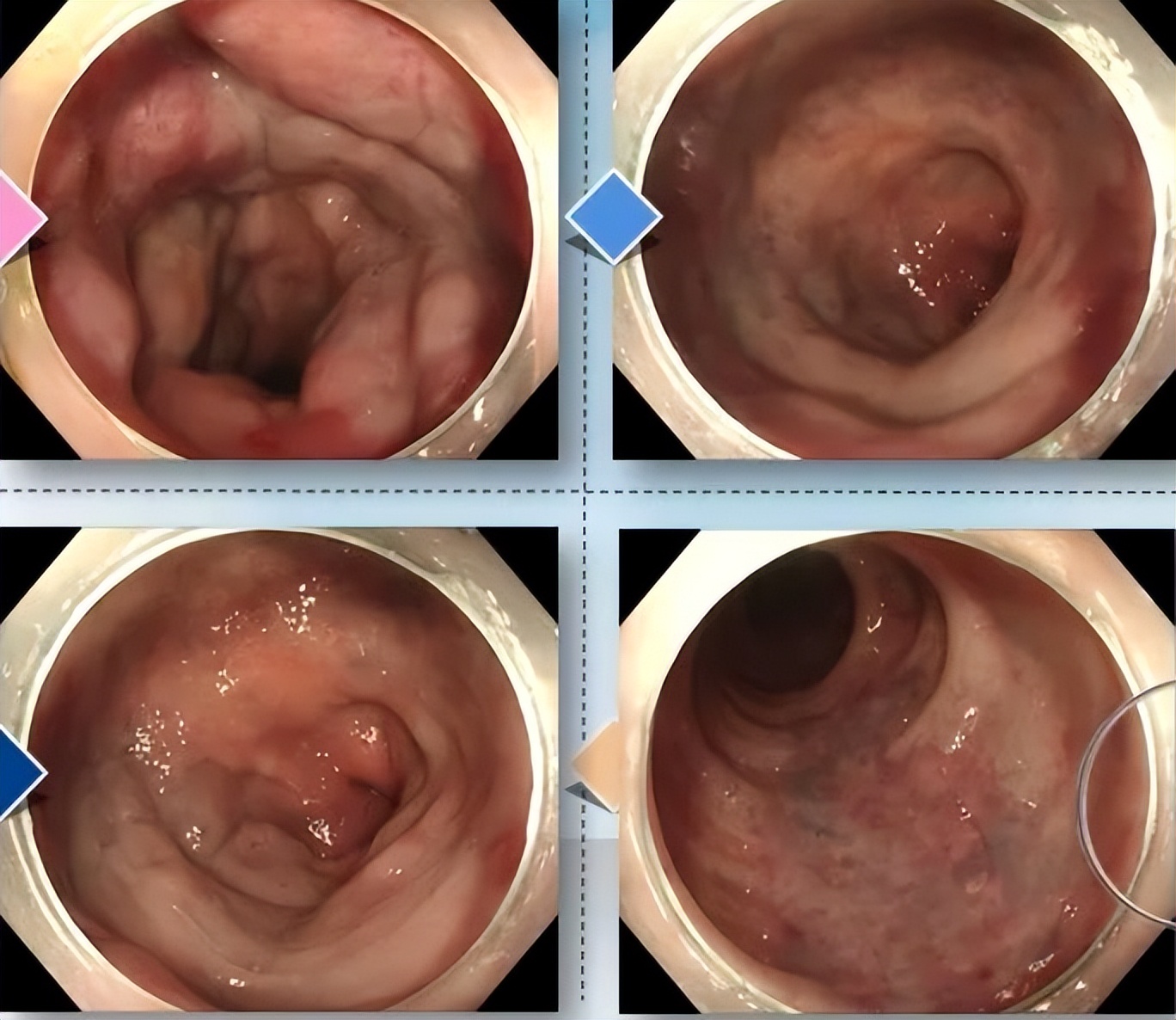

Electronic colonoscopy report indicates: Diffuse patchy superficial elevations are observed in the rectum, appearing dark red or light blue, with scattered erosions and red capillaries on the surface, showing significant congestion and edema, consistent with manifestations of rectal vascular malformation.

Examination selection logic: start with non-invasive methods before proceeding to invasive ones

For asymptomatic patients with hematochezia, first perform contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. If vascular dilation is indicated, follow up with endoscopic ultrasound evaluation. For cases of persistent bleeding, proceed directly with angiography to quickly locate the bleeding site and gain time for emergency hemostasis.

III. Diagnosis and Treatment: A Scientific "Two-Step Approach"

Diagnosis: Three Major Criteria to Avoid the "Misdiagnosis Pit"

All three criteria must be met simultaneously: ①Symptoms: Painless recurrent hematochezia (bright red blood coating stool surface or dripping blood, without mucus or bloody pus) persisting for over 2 weeks or unresponsive to medication; ②No definitive cause found on routine examinations (digital rectal exam, conventional colonoscopy); ③Imaging/endoscopy reveals rectal vascular ectasia (diameter ≥3mm).

Particular differentiation needed from three disease categories:

Internal hemorrhoids: Often accompanied by anal prolapse and defecation pain (thrombosed hemorrhoids), colonoscopy shows hemorrhoidal protrusions without vascular dilation;

Ulcerative proctitis: Accompanied by abdominal pain, mucopurulent bloody stools; colonoscopy reveals mucosal erosion and ulcers, with pathology showing inflammatory cell infiltration;

Rectal cancer: Accompanied by weight loss (more than 5% in 6 months), changes in stool shape, and pathological detection of cancer cells.

Treatment: Select the optimal approach in stages

Endoscopic treatment (preferred, suitable for 80% of patients):

Sclerosing agent injection (e.g., polidocanol, sodium morrhuate): The drug is injected into the dilated blood vessels through a colonoscope, causing endothelial damage and thrombus formation. The blood vessels close within 1-2 weeks, with an effectiveness rate of 90%. Mr. Zhang received this treatment, and his rectal bleeding stopped 3 days after the procedure.

Rubber band ligation: Using elastic bands to ligate the base of blood vessels, cutting off blood flow. The ligated tissue necrotizes and falls off within 7-10 days. Suitable for isolated vessels with diameter <5mm, with a recurrence rate of only 4%.

Surgical resection of the rectum (for severe cases): Colorectal vascular ectasia patients who meet the following criteria may consider surgical intervention: 1. Recurrent lower gastrointestinal bleeding; 2. Or chronic anemia; 3. Mesenteric angiography confirms bleeding caused by colorectal vascular ectasia, with extensive vascular dilation (exceeding half the rectal circumference) and clearly identified lesion sites; 4. Cases where non-surgical treatment or endoscopic therapy is ineffective, or patients with massive bleeding (hemoglobin <70g/L) experiencing recurrent hemorrhage.

Management of underlying conditions: Patients with cirrhosis should take β-blockers (e.g., propranolol) to reduce portal vein pressure, while those with chronic kidney disease need to control serum creatinine levels (<178 μmol/L) to prevent worsening vascular damage.

IV. Prognosis and Prevention: The "Guardian Guide" for Long-Term Management

Postoperative strict follow-up is required: initial re-examination at 3 months post-surgery (endoscopic ultrasound to assess vascular status), followed by annual colonoscopy for 5 years—if no recurrence occurs, the interval may be extended to once every 2 years. Lifestyle modifications are key for prevention: daily intake of 25-30g crude fiber (such as oats, celery, or dragon fruit) and 2000-2500ml water, avoid prolonged sitting exceeding 1.5 hours (take 5-minute activity breaks every hour). Patients with chronic constipation may take lactulose long-term (15-30ml daily) to soften stools and reduce vascular friction damage.

One month after the operation, Master Zhang has picked up the steering wheel again. Now, his cab holds an insulated cup (filled with dietary fiber powder) and a timer—parking every 1.5 hours to walk two laps around his truck. "Turns out bloody stool is no trivial matter. Only by identifying the root cause can you truly feel at ease," he says.